-

-

Metal One’s businesses and roles

-

Plate, Construction & Tubular Products Business Division

-

Flat Products Business Division

-

Global Business Division

-

Global Marketing & Energy Project Business Division

-

Wire, Specialty & Stainless Steel Business Division

-

Digital transformation

-

Carbon neutrality

-

Business creation and innovation

-

-

Recruiting information

-

Terms of Use

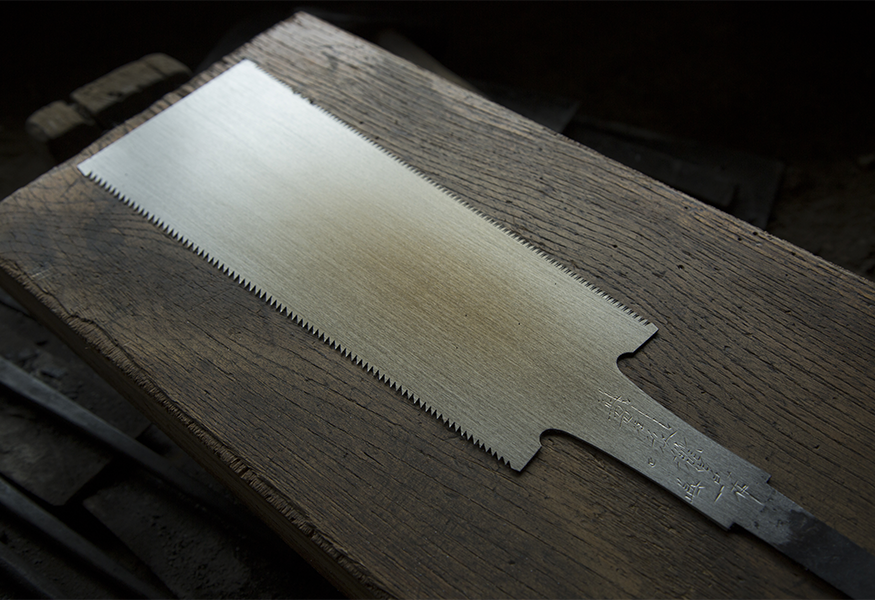

Saw smithy

Saw smithy

Kawagoe

Carrying on a Tradition That Started at the End of the Edo Period

With every blast of air from the bellows, sparks from the pine charcoal that has been heated red-hot go soaring into the air like fireflies. This is the saw smithy of Mamoru Ito—a fifth-generation artisan whose professional name is Ryujiro Masayoshi Nakaya. Located in Kawagoe, Saitama Prefecture the smithy has operated since the waning days of the Edo Period (1603–1868) around 165 years ago.

These days you rarely get to see sawyers’ wide-blade ripsaws being used to cut lumber. There are also very few artisans who can repair these large saws made before the Second World War. Since they are too big to fit in the furnace, the blade is gripped between red-hot pincers and tempered when the heat transfers. Repeating this task for each blade calls for patience and great concentration.

Kawagoe is called “Little Edo” for the Edo Period atmosphere it has retained. The first Ryujiro Nakaya started his saw smithy in this area in 1853, and prospered in the castle town of the Kawagoe clan. The first-generation’s smith reportedly came to Kawagoe after training in Kounosu, in the year that Admiral Matthew C. Perry’s “black ships” arrived in Uraga.

Around 120 years from then Ito, who was in the Self-Defense Forces, apprenticed himself to the fourth-generation smith at the age of 23. “I saw an older-generation saw I thought was beautiful, at a time when I wanted to find work making things by hand,” he recalls. “Because of that, I leapt into this world.” Carrying on a traditional craft since that day, he became one of the few smiths that still handcrafts saws one by one.

Demand for handsaws has declined due to the spread of power circular saws, but even now orders come from around the country from craftspeople such as shrine and temple carpenters who prefer authenticity. He also receives many requests for repairs of wideblade ripsaws and other old saws. “Orders from overseas have also been on the rise recently,” he notes. “I’ve also received an order for a special type of saw from a violin artisan in the U.S. Japanese saws cut with precision and are highly valued in other countries as well.”

Ito has changed the traditional techniques he learned from his predecessor very little. The best example is the process of hardening and tempering, which Ito says is the most difficult and crucial. Several times a year he closes all the smithy’s shutters in the morning and silently faces the fire alone in pitch darkness. He determines by its color whether the temperature of the fire is at the 800ºC or so said to be appropriate for tempering. “A saw’s degree of perfection depends on the quality of hardening and tempering,” he says.

Through many long years, Ito still carries on the craft in its essential form, making hard, flexible, beautiful saws.

Value One 2019 No.65